Michael Barrier

Michael Barrier has quite a few interesting emails and links lately; one that pushed one of my animation hot buttons grew out of his and others' reactions to "Ratatouille". It involves the handling of animals as characters in animation. Mike links to a post by caricaturist, Sheridan College instructor and blogger

Pete Emslie. Pete's thoughts are fairly brief but clear and pointed, and as he says, there are many permutations to the types of characterizations he lists in his post.

Barrier himself writes something I couldn't put any better:

"To me, anthropomorphism like that in so many Hollywood cartoons has most often been a sign not of infantilism—the common accusation—but of an openness to the potential of artistic devices that more fastidious minds reject out of hand. You can do things in animation and the comics with animal characters that you can't with human characters; and as Pete's handout suggests, the more alert the artist is to the possibilities and limitations inherent in the different kinds of animal characters, the better the odds that something exceptional will result."

Boldface is mine. The misuse or dismissal of this truism Barrier mentions has frustrated me in the process of doing story on a couple of projects in the past, before my present job.

There were instances where opportunities to add something special were missed, involving animal characters that while able to "talk" didn't ever speak to human beings and were supposed to be real animals in a "real" environment.

Those projects worked from a script, but there was (supposedly) ample room for some visual, physical interpretation and ideas from the story artist. In some cases, however, I found myself thinking that the characters--instead of being birds or dogs--could have been mice, cats, horses or buffalo and virtually

nothing but the character design would have changed.

There was literally no thought given to how a

dog would react to a situation versus a parrot. It was all plot and dialogue, all the time. The fact that a story might revolve around a canine in a human household was only a gloss, not the crucial factor it should have been.

As someone who's lived with dogs, parrots, horses, fish and cats(to name a few), this really drives you around the bend in its waste of potential animation gold just sitting there waiting to picked up, drawn and presented to the audience. So, whether it makes it into the film or not, you continually try to insist on not just having a character get from A to B, but have him get there the way a puppy would. This doesn't mean cramming all kinds of diversions and asides into a scene but being judicious about where, when and how much depending upon that character at that moment.

Few films achieved this as brilliantly as in the handling of all the animals in "Lady and the Tramp". It's a lesson in thinking along those lines, and in the process turns scenes that might be a heck of a tough sell today("they put the puppy to sleep in the kitchen with a newspaper, but she won't stay put") and turns it into

the universal, lovingly familiar experience that everyone who's ever raised a dog has experienced--and as a bonus we get to see it from not only the humans' but the

puppy's point of view. It's scenes like that, just as much as the old "Bella Notte" number or "He's a Tramp" that make this a classic. Incidentally, those musical numbers are both examples of the story crew really pushing the limits they've set for themselves in terms of how anthropomorphized the dogs are--but (in my opinion at least) they get away with it as they do all through the film by never leaving out the "dogginess" they need to sustain the fantasy and tether it to reality.

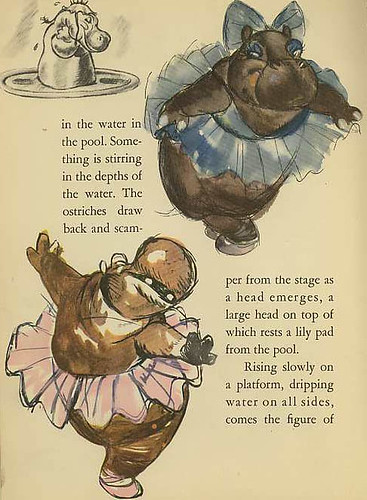

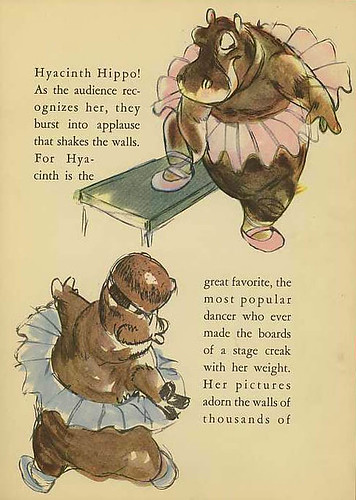

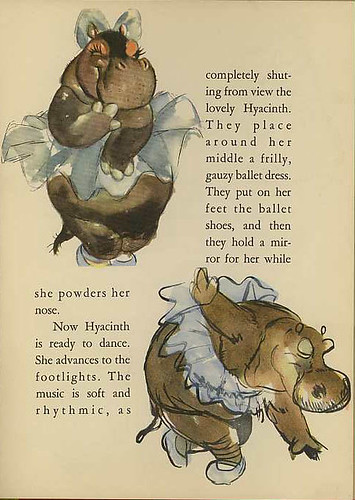

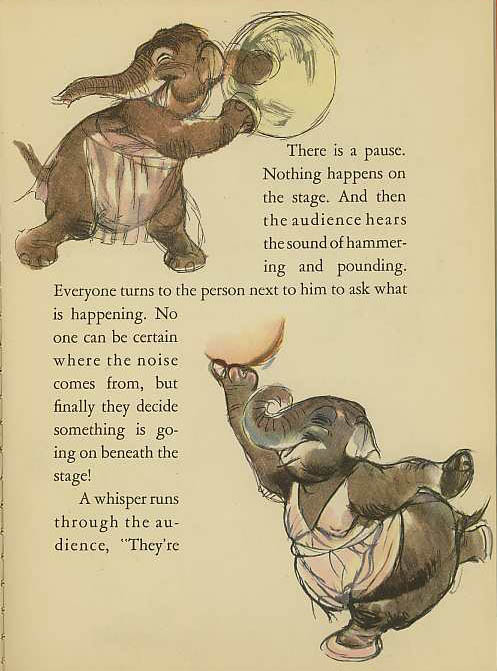

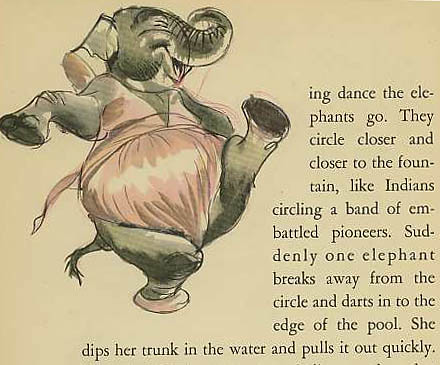

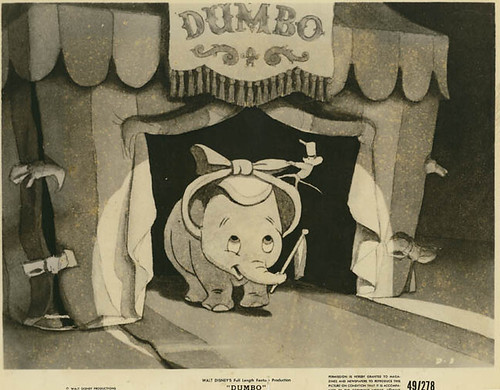

This isn't to say that degrees of "faithful" anthropomorphism can't be mixed within a film with success in the best efforts of animation. I stumbled on a bit of "Dumbo" on TV yesterday, and the crows, Timothy Mouse and the Stork have little relation to their real life counterparts other than the use of their wings-those that have them-and the fact that they

have beaks or tails. In "Dumbo" the brasher characters are also "free"--free of the strictures of being working circus animals, they can come and go as they wish and boss about or rag on human beings and animals alike, acting as a Greek chorus. They exist in a kind of limbo between the "real" elephants and kangaroos and tigers and the full-on humans such as the ringmaster. Timothy would gain little or nothing to push more elements of real mouse onto him--he doesn't need it. He's more [Fred]Moore than Mouse.

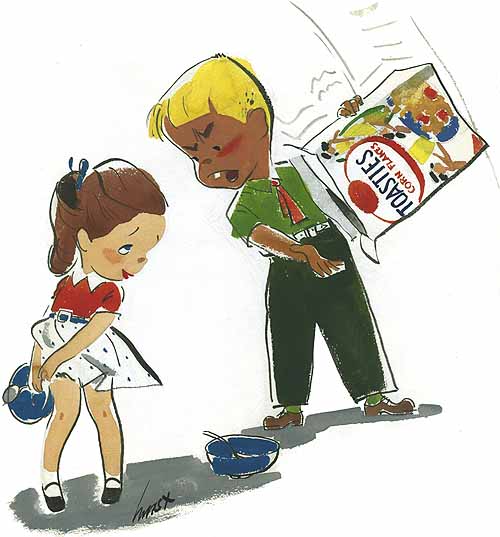

images courtesy of this site

images courtesy of this siteObviously one could go on about this all day--"Ratatouille" offers a lot to chew on on this subject, and I've already written a bit here and elsewhere about how well I thought those animals were handled, with attention paid to extreme subtleties of rats that made for an almost subliminal layer of reality to Remy and the others(but especially Remy). I don't know how much was instigated by the animators, but knowing Bird I would surmise that there are no accidents in anything on that score; the phrase "with a gimlet eye" was invented for Brad Bird, believe it.

Still, there are some shots where I'd sure like to wring that animator's hand.

photo of Scott Morse by Jim Capobianco, courtesy of his blog

photo of Scott Morse by Jim Capobianco, courtesy of his blog