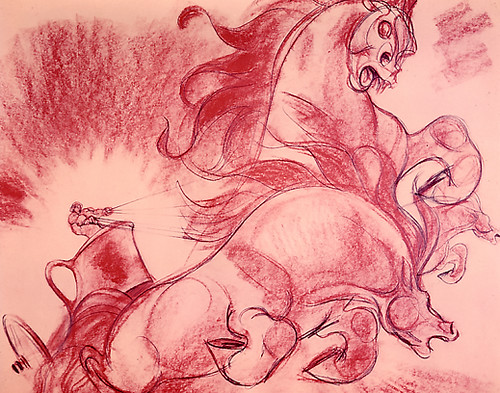

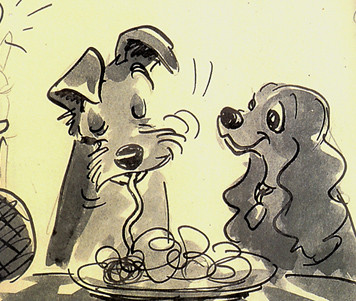

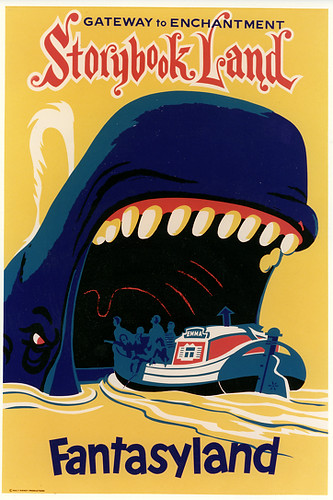

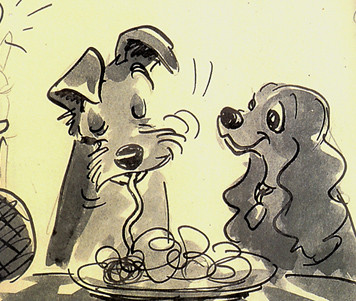

From the book "Paper Dreams": an unattributed story panel for "Lady and the Tramp"

From the book "Paper Dreams": an unattributed story panel for "Lady and the Tramp"Last night I went to see the restored, remastered, generally-spiffed-up rerelease of "Lady and the Tramp" at the El Capitan theater in Hollywood. I've seen it at least once before theatrically, but never in

Cinemascope, the widescreen process it was originally designed for. Watching this film again under optimum conditions is a terrific experience.

It would be difficult to sell a story as simple as "Tramp" is today. Even among Disney features it's remarkable for how little happens, plotwise: A puppy starts life with a middle class young couple; the couple has a baby, the dog feels briefly unwanted; she meets a dog from "the wrong side of the tracks"(literally); they have a romance, some misunderstandings, and the story ends with them both as happy members of the family circle with pups of their own.

That's it.

And it's about as far as one can get from high concept. Not that there's anything wrong with high concept per se; "The Incredibles" is a great example of such a premise that adds up to a lot more than a one-line pitch: "retired, incognito superheroes with a suburban family lifestyle are jolted into action once more, with kids". In fact, a story as seemingly postmodern and slick as "Incredibles" actually has a lot in common with "Tramp"--more on that in a minute.

Where "Lady and the Tramp" succeeds is in taking a simple story and making absolutely sure that every character and every scene makes an impact on the audience. As leisurely as some of the pacing is, it's deliberate and crucial to establishing the mood--either of the time period, the time of day, or the characters' emotions. And there is very little dialogue--as well as the fact that it's not so much

what the characters say, but how they act while saying it. The humor comes from context and

expression,

not from verbal jokes. When old bloodhound Trusty offers to launch into another rambling story and asks rhetorically if he's told this one before, and Jock the Scotty replies "Aye, ye

have, laddie", the remark gets a big laugh--not because of any reference other than the familiar expression of friendly, slightly chagrined resignation on Jock's face. Which brings up another neat trick of "Tramp": it manages to tell the story of a dog, from a dog's point of view, anthropomorphizing dogs so that we recognize ourselves in them while at the same time keeping their essential dogginess front and center.

That sounds pretty simple, and yet with some films it can seem that it wouldn't matter if the characters were dogs--or whether they were birds or pillbugs. And it

should matter. Admittedly there are different kinds of films where the humor and approach is slanted a different way and there's a different kind of story being told.

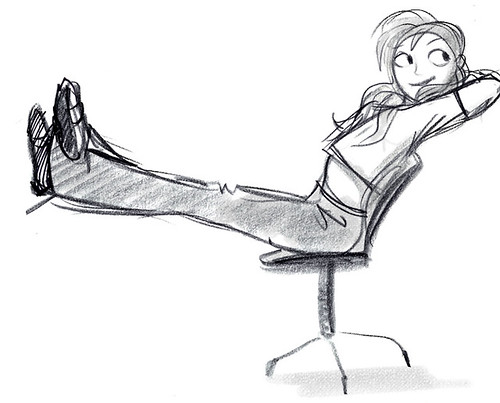

But speaking as a story person, the fun of using animals is partly in things like imagining how a cat might walk into a room versus a dog(as beautifully illustrated in "Tramp" with the siamese cats scene). And the fun for an audience is in recognizing those details. Even if the character is a human stand-in a la Disney's Brer Rabbit, his rabbity body can suggest poses and behavior he wouldn't do if he were a stork. Some things fall into the purview of the animator, but when story artists

think like animators--imagining the scene playing out in their heads--gags, action and completely new ideas come out of the blue. Have a strong basic structure, a story that can be told well and clearly, and most of all, strong characters that one cares about, and

they dictate to you what they're going to do next--

you have the fun of reining them in. What often happens with this approach is that there's an excess of--you hope--riches; many scenes get cut, all sorts of things are changed...but if the characters are well defined and real, it'll be hard for the scene to go wrong. That's the ideal, anyway.

So getting back to "The Incredibles": on the surface it's a much more sophisticated and complicated film than the gentle, easygoing "Lady and the Tramp"--but the story principles are exactly the same, and what make both films work so well each in their own way. It all boils down to "what is this scene

about?" Dialogue might get important points across, but more often it's there to express the characters' emotions, not describe what we're already seeing--and sometimes outright contradicting it to great effect. The basic plot was carefully constructed--really iron-clad; any number of various, interchangeable adventures could have followed Mr. Incredible arriving on the mysterious island, but what matters is how he, his wife and his kids will handle getting involved in whatever ensues.

The director of that film was also the writer, and had plenty of professional experience writing specifically for animation(one of his trump cards as a writer is knowing what to leave

out of his scripts), but I would bet that he also anticipated and consciously left enough room to allow for alterations in the storyboard process to further the characters and story where necessary. The director/writer thought up loads of cool scenes, created opportunites for fantastic production design and certainly laid on the action, but he never lost the basic--and super simple--family dynamic and vivid personalities that made the action and the cool designs mean anything. Some people will watch nifty graphics and be satified with that alone; most will get plenty bored and never be tempted to watch a film twice,

unless it puts across that X factor of simplicity and sincerity that will hold up whether its a sci-fi or an edwardian setting.

Animation feature production is by necessity a group endeavor, with the end result--or goal--being a single vision and cohesive piece of entertainment. It's organic and often unwieldy. Scenes are commonly tried, boarded, written and rewritten, and restaged by many different artists. Naturally enough, sometimes the story person finds that a scene has lost its meaning through these multiple versions and reboardings and edits...and so it always comes back to the most basic, simple question: what is this supposed to be

about? It's a strikingly simple question, and the answer should be simple as well. Answering that honestly can mean taking a wild leap beyond what's already been done, but it can pay huge dividends.