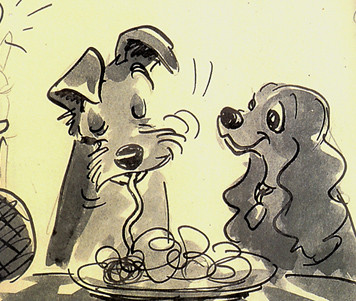

From the book "Paper Dreams": an unattributed story panel for "Lady and the Tramp"

Last night I went to see the restored, remastered, generally-spiffed-up rerelease of "Lady and the Tramp" at the El Capitan theater in Hollywood. I've seen it at least once before theatrically, but never in Cinemascope, the widescreen process it was originally designed for. Watching this film again under optimum conditions is a terrific experience.

It would be difficult to sell a story as simple as "Tramp" is today. Even among Disney features it's remarkable for how little happens, plotwise: A puppy starts life with a middle class young couple; the couple has a baby, the dog feels briefly unwanted; she meets a dog from "the wrong side of the tracks"(literally); they have a romance, some misunderstandings, and the story ends with them both as happy members of the family circle with pups of their own.

That's it.

And it's about as far as one can get from high concept. Not that there's anything wrong with high concept per se; "The Incredibles" is a great example of such a premise that adds up to a lot more than a one-line pitch: "retired, incognito superheroes with a suburban family lifestyle are jolted into action once more, with kids". In fact, a story as seemingly postmodern and slick as "Incredibles" actually has a lot in common with "Tramp"--more on that in a minute.

Where "Lady and the Tramp" succeeds is in taking a simple story and making absolutely sure that every character and every scene makes an impact on the audience. As leisurely as some of the pacing is, it's deliberate and crucial to establishing the mood--either of the time period, the time of day, or the characters' emotions. And there is very little dialogue--as well as the fact that it's not so much what the characters say, but how they act while saying it. The humor comes from context and expression, not from verbal jokes. When old bloodhound Trusty offers to launch into another rambling story and asks rhetorically if he's told this one before, and Jock the Scotty replies "Aye, ye have, laddie", the remark gets a big laugh--not because of any reference other than the familiar expression of friendly, slightly chagrined resignation on Jock's face. Which brings up another neat trick of "Tramp": it manages to tell the story of a dog, from a dog's point of view, anthropomorphizing dogs so that we recognize ourselves in them while at the same time keeping their essential dogginess front and center.

That sounds pretty simple, and yet with some films it can seem that it wouldn't matter if the characters were dogs--or whether they were birds or pillbugs. And it should matter. Admittedly there are different kinds of films where the humor and approach is slanted a different way and there's a different kind of story being told.

But speaking as a story person, the fun of using animals is partly in things like imagining how a cat might walk into a room versus a dog(as beautifully illustrated in "Tramp" with the siamese cats scene). And the fun for an audience is in recognizing those details. Even if the character is a human stand-in a la Disney's Brer Rabbit, his rabbity body can suggest poses and behavior he wouldn't do if he were a stork. Some things fall into the purview of the animator, but when story artists think like animators--imagining the scene playing out in their heads--gags, action and completely new ideas come out of the blue. Have a strong basic structure, a story that can be told well and clearly, and most of all, strong characters that one cares about, and they dictate to you what they're going to do next--you have the fun of reining them in. What often happens with this approach is that there's an excess of--you hope--riches; many scenes get cut, all sorts of things are changed...but if the characters are well defined and real, it'll be hard for the scene to go wrong. That's the ideal, anyway.

So getting back to "The Incredibles": on the surface it's a much more sophisticated and complicated film than the gentle, easygoing "Lady and the Tramp"--but the story principles are exactly the same, and what make both films work so well each in their own way. It all boils down to "what is this scene about?" Dialogue might get important points across, but more often it's there to express the characters' emotions, not describe what we're already seeing--and sometimes outright contradicting it to great effect. The basic plot was carefully constructed--really iron-clad; any number of various, interchangeable adventures could have followed Mr. Incredible arriving on the mysterious island, but what matters is how he, his wife and his kids will handle getting involved in whatever ensues.

The director of that film was also the writer, and had plenty of professional experience writing specifically for animation(one of his trump cards as a writer is knowing what to leave out of his scripts), but I would bet that he also anticipated and consciously left enough room to allow for alterations in the storyboard process to further the characters and story where necessary. The director/writer thought up loads of cool scenes, created opportunites for fantastic production design and certainly laid on the action, but he never lost the basic--and super simple--family dynamic and vivid personalities that made the action and the cool designs mean anything. Some people will watch nifty graphics and be satified with that alone; most will get plenty bored and never be tempted to watch a film twice, unless it puts across that X factor of simplicity and sincerity that will hold up whether its a sci-fi or an edwardian setting.

Animation feature production is by necessity a group endeavor, with the end result--or goal--being a single vision and cohesive piece of entertainment. It's organic and often unwieldy. Scenes are commonly tried, boarded, written and rewritten, and restaged by many different artists. Naturally enough, sometimes the story person finds that a scene has lost its meaning through these multiple versions and reboardings and edits...and so it always comes back to the most basic, simple question: what is this supposed to be about? It's a strikingly simple question, and the answer should be simple as well. Answering that honestly can mean taking a wild leap beyond what's already been done, but it can pay huge dividends.

23 comments:

Hi:

This is an absolutely brilliant posting. Maybe I say that because I agree with you, basically. I don't think that ,The Incredibles is as masterful in its storytelling as Lady & The Tramp. The first half of Brad Bird's film is every bit as good, but once it gets into the adventure part, the film weakens a bit. It's still great, but there's never the tension that the rat scene in L&T offers.

Thank you for this posting, it's just superb.

That's just one of the things that would prevent the Eisner Disney from making Lady and the Tramp today. The other, even more painful reality is that Lady and the Tramp just drips with good taste. You cannot teach good taste.

No rapping fish or skateboards- just a good story.

Compare Bambi to Bambi II if you doubt this.

Wow! Beautifully written post! I eagerly check your blog everyday for a new post and this one floored me! Thanks for the inspiration.

There is a moment during an interview with Brad Bird on the Incredibles DVD extras that illustrates the importance of each scene in a film. He was talking about how you can have a bit in a scene that you may have had since the beginning, something everyone laughed at in each test, something you held onto tightly throughout production. Once that bit is lined up with other scenes sometimes it doesn't work, having the ability to let that beloved bit go can make all the other scenes snap in place. I'm paraphrasing, but essentially that decision to chuck a bit to the floor, despite what it may have cost developing it to that point is a very tough call to make as a filmmaker during production. The sense of loss at that time is always overcome by seeing the film in its entirety. It is then when it is easier to be aware of how every detail in every moment is important, how every scene creates a door for each character to walk through and be someone new on the other side of the threshhold.

"What does this scene mean to the characters?" would be the phrase that should propel each division in production. Brad Bird is very aware that that question should effect every stage of production,from script to render, and it is very evident to me that millions of little decisions were made with the concerns of the characters reaction to themselves and each other first and not upon "How do we fit this joke/gag in?"

I think too many productions on the market today hold onto those bits,strong (or weak) as they singurlarly are, forcing words into their characters mouths, denying them their own honesty.

You've made a very insightful post, let's hope it reaches the people that could use it the most.

Thank you.

Very well said.

As an aspiring animation director/writer, I am always trying to pick up as much as I possiblly can from people already in the industry. And I think I have found one of the most difficult things, for me at least, to do starting out, is keepin my ideas simple and clear. I often have so much I wanna say and do, that I struggle with the challenge of channeling it into one clear and simple story.

But sifting through everything, and reaching the point where you say "That's it!," certainly makes the whole process worth it.

I can only imagine how the L&T crew felt when it happened to them, as well as the Pixar guys.. with just about every film they've done :)

The blogging world has been an amazing source of insight, as well as inspiration and I appreciate your post.

All the best!

Dan

Hello!

This post I think is right on the money.

There was a kind of inspiration, a willingness to experiement with storytelling with "Lady". It was about a place and a time, and the emotional experiences of a dog (that most children and adults can identify with).

I think the magic comes not from mathematically constructing the perfect story (as so many stuudios try to do these days), but from inspiration and the willingness to let the character exist in a natural way.

Great post!

-M

I'm not one for words. Well, thought out and making sense words, anyway...but I'm glad that there's someone out there, probably many, who, like you, are able to express what I feel for animation. I love your insight and observations. Thanks for posting. Keep it up

Well done!

Especially the last paragraph. In my limited efforts in feature animation boards, that simple question proved elusive to many people involved; often people contradicted each other to the end edit, which was worrisome.

I'm looking forward to hearing more.

Thanks,

~ w.

Terrific post. --You know there's another issue involved in great storytelling which I think might be implicit in your article: Thematic Content. Stories stay with us because they reinforce some core value. They are indeed About Something. They may in fact be telling us something we already know ("Families are important", "Honor is a necessary virtue" etc. etc.) but we humans like to be reminded of those things. It's because movies like "Star Wars" and "Lady and the Tramp" have that Thematic Content that we're watching them literally decades after they were made. It's because movies like "Shark Tale" DON'T have that confirmation of some core value that we lose interest in them the day after we've seen them.

I don't know how many people deliberatly set out to deliver a Theme (there is that old saw "If you want to send a message, call Western Union") but writers would do well to at least consider what aspect of life it is that they're seeking to comment on. Affirmation of core values can make all the difference between longevity and complete disposability.

Excellent observations! I could not agree with you more and it fills me with happiness(validation?) that there is... someone... out there with the same sensibilities as me.

i've worked in the industry for ten years and i feel like the same convictions have made me a pariah.

I even developed a short of my own (with no dialogue) into a highly elaborate animatic and more than one industry exec explained to me that they loved it and they loved the story, but frowned because i had no dialogue.

Like i was somehow shirking the task of putting dialogue into it. Like it was easier to convey the story with no dialogue...

crazy.

thanks for your comments.

I, too, really enjoyed seeing Lady and the Tramp at the El Cap. Kept trying to promote it on my site hoping other people would go see it there too. So much better than watching it on a TV. Another thing Brad Bird has said is, "Don't be afraid to slow the story/action down from time to time."

Tom Dougherty said, "That's just one of the things that would prevent the Eisner Disney from making Lady and the Tramp today."

The Eisner Disney is slowly dissolving.

In case anyone has yet to mention this, when one is storyboarding from a "final" script, the first and most important question to ask is "What are they trying to say?" Then one must visaully say it. The writer and tastemakers above the writer should have already asked the question "Is this scene necessary?", but that would mean we were living in a perfect world.

Thank you, everyone, for the wonderful encouragement and feedback--I really appreciate it. There's so much to say on this huge subject(story)that I was more than a little afraid it would either be too short, too long or too little something else. I'm humbled by the reaction. : )

re: the last comment above by 'anonymous'; yes, you're quite right--but keep in mind that in feature animation story the script is generally regarded as much more of a starting point or template than in a live action film--a lot more; it's perfectly normal and expected that the script is going to change considerably as it's translated into visuals. As brilliant as a writer may be, it's virtually impossible to write down everything that an animated film needs on the screen to tell its story. I include myself; as much as I've boarded, and as much dialogue as I've written, and scenes that I've conceived myself on paper(that is, before drawing), I still could not sit down and cover every visual angle of a film, alone. That's the strength of storyboarding and the pitching process which I'm going to write about next. No matter how good a scene is on paper, no matter how much care has been taken--there's often an idea that comes out of nowhere that either improves or just plain changes the scene--and 99% of the time those ideas are from the fresh eyes of the rest of the story crew, the directors--really anyone with an intimate knowledge of the overall story.

"What's this scene about" applies to all sorts of storytelling genres. An illustrated book or comic needs to do the exact same thing: "what's this page about" or "what's this panel about." This is a great reminder for those telling stories; make what you do, count.

I love that you wrote this, because I was showing my nieces Bambi yesterday and thought THE EXACT SAME THING! It's been years since I watched Bambi, and yesterday I started to show them Bambi II because I just bought it... but they mentioned they'd never seen Bambi before. I was amazed that my nieces never once laughed at the dialogue. It was wordless actions that had them giggling. I thought, wow, what a big contrast from animated movies now that rely so heavily on jokes. And on top of being a film that isn't driven by dialogue, it also doesn't have much of a plot (not what passes for a plot nowadays, at least). Bambi II had its moments, but I was disheartened because Bambi's transformation into an action hero really didn't fit the theme of the original film. It was no longer a portrait of one deer's life in the wild... it was just another animal adventure movie. It's sad to think that a film as endearing and well crafted as Bambi probably won't hold the attention of modern moviegoers, simply because it doesn't move fast enough.

Great post! Lady and the Tramp does maintain a perfect anthropomorphic balance of dogginess and humanity. And, did Disney character animation ever get any better than in this movie? I don't think so.

That was lovely to read! It helped clarify some of my own reactions to the films you mentioned. I look forward to your next post. :)

I have Paper Dreams, too. Great book. Bill Peet was my favorite.

Dave

Hi,

Great post indeed!

Regarding “the fun of using animals”: one of my favorite sequences in “Aristocats” involves O’Malley exercising his charm on Duchess (right until she mentions her kids…). The thing that blows my mind in that scene, is that his “male charm” is distinctly that of a cat male – it can’t be mistaken for human body language (he’s rolling on his back for her!), not even for a doggish one. Yet, it certainly communicates male charm to us as human beings. Like all ingenious things, it may looks obvious once you’ve seen how it's done – but I think it takes one hell of an artist to pull off something as delicate as that.

Awesome post! Thanks for articulating what a whole lot of us had been thinking!

eloquently put and very insightful!!

BRILLIANT post! Wonderful... I wonder what you might have to say about Studio Ghibli films... Hayao Miyazaki's films seem to be much broader in their size and scope than western animated films... And yet, I love these films just as much as I do the classic Disney films.

Bill Peet, I think is the "unnatributed story artist".

Post a Comment