Published on 9/17/08:.

Bob Winquist dies at 85; influential animation teacher at CalArts

By Valerie J. Nelson

Los Angeles Times Staff WriterSeptember 17, 2008

Bob Winquist, a former director of the character animation program at California Institute of the Arts who greatly influenced a number of animators now working in Hollywood, has died. He was 85.

Winquist died Sept. 10 of complications related to old age at an assisted-living facility in Simi Valley, said his niece, Joyce Snyder.

He was the kind of inspirational teacher that movies are made about, said his former students, who went on to make films that reflected lessons learned in his Valencia classroom between 1983 and 1991.

Ralph Eggleston, who won an Academy Award in 2001 for his animated short "For the Birds," credits Winquist with pushing students to think more broadly about what they could accomplish.

"When Bob came in, animators primarily left the school and became animators. Suddenly, they started becoming art directors and storyboard artists. He made us think of ourselves as filmmakers, not just animators," Eggleston told The Times.

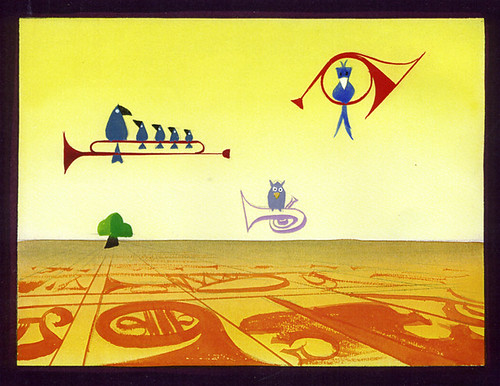

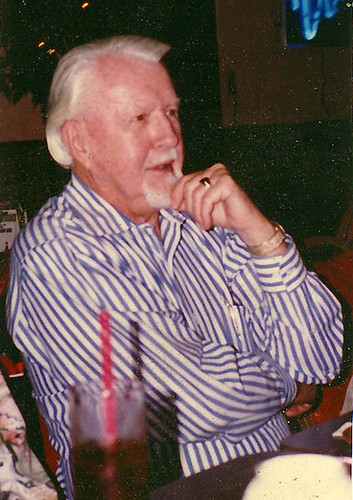

The dapper Winquist might stroll into class, announce the lesson by saying "develop the character of the letter 'A' " and then walk out, leaving the young animators to puzzle out the assignment.

Pete Docter, a former student who wrote the story for the film "WALL-E" (2008) and directed "Monsters Inc." (2001), considers Winquist "a seminal person in my development as an artist and a person."

"He had a gentle and inviting way -- you felt intrigued. It was like he was saying, 'You go discover it yourself,' and it made things stick," Docter said.

A world-class raconteur, Winquist often captivated his classes with hard-to-verify recollections that often placed him Zelig-like at memorable moments in Hollywood history. Witnessing the burning of "The Gone With the Wind" set, designing a suit for Elvis Presley, "baby-sitting" Marilyn Monroe on the set of "Some Like It Hot" -- these were all first-person stories that could be woven into a lecture.

"In the end, it didn't really matter if he were there because his amazing stories made me think . . . I can go out and do anything," Docter said.

Winquist often eschewed credit for his work because he valued his privacy, his family said.

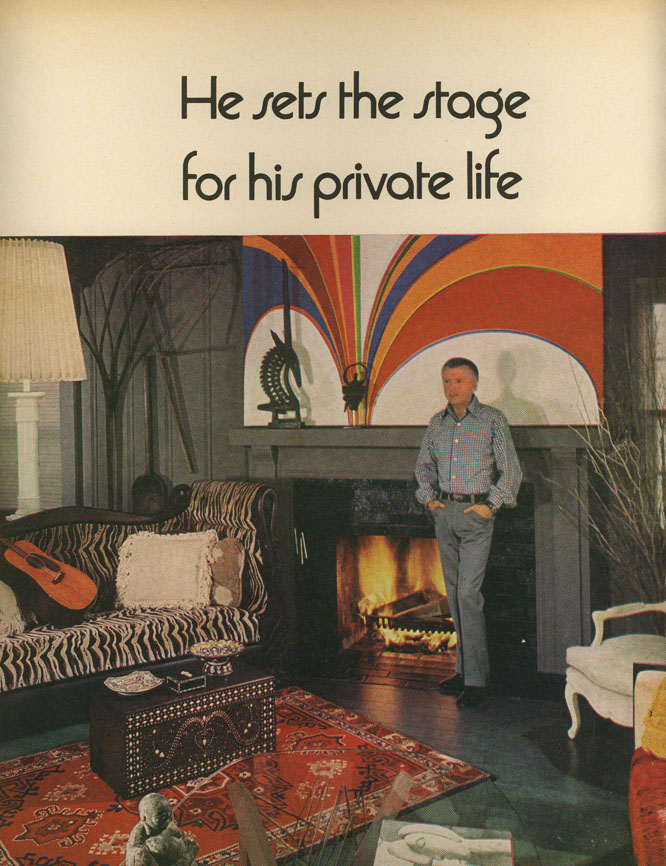

Trained as a designer, he studied at Cambridge University and ran a design firm with Robert Hammer, an artist who was also his life partner. They spent about 50 years together, living in Manhattan Beach and Valencia, before Hammer died about four years ago. Winquist has no immediate survivors.

According to a 1971 Times article, Winquist designed "everything from movie sets to diapers."

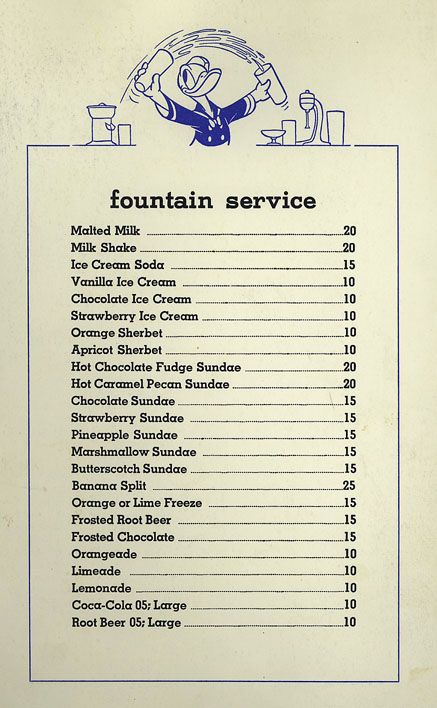

His family has photographs of him working on Main Street and plans he drew of Disneyland's main thoroughfare.

Winquist was known for his intricate paper sculptures and exhibited in France, Britain and the U.S., The Times reported in 1960.

As an interior designer, his work was featured in The Times in the 1950s and 1960s, and his celebrity clients included Gene Hackman.

Robert Amos Winquist was born Aug. 15, 1923, in Kansas City, Kan., one of six children of Adolph and Margaret Winquist. His father was a mortician.

Raised mainly in California, Winquist served in the Army Air Forces as a ball-turret gunner during World War II.

He also relied on his artistic talent to paint the noses of B-17 bombers, his family said.

He taught for 15 years at the Chouinard Art Institute, which merged with the Los Angeles Music Conservatory to become CalArts in 1961.

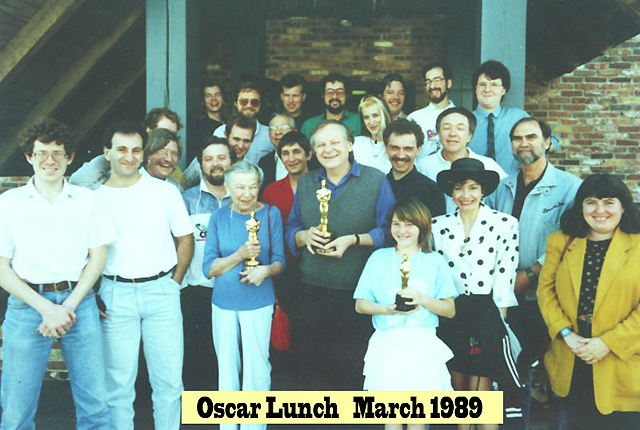

At CalArts, he taught color and design before heading the character animation program from 1989 to 1991.

Students "flocked to him like gremlins," said John Bache, an associate provost at CalArts.

"His low-key approach to teaching, plus the personal contact, made him a great teacher," he said.

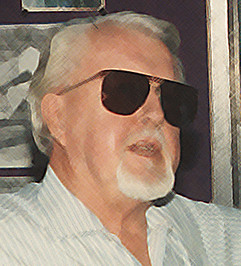

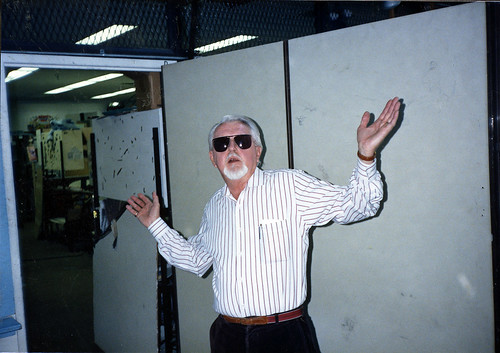

The dark sunglasses he invariably wore only added to his mystique as he held court on must-see films or tossed off references to classical art.

Jenny Lerew, a former student and story artist at Disney, wrote in an e-mail: "He made us all believe every good thing could happen to us -- if we put ourselves 'in harm's way' first. . . . "

He was a "cheerleader for their futures," Eggleston said, one who came to campus in his butter-yellow Mercedes-Benz with the license plate frame that read: "I'd rather be flying."