More about the Mary Pickford film I saw recently, and why I think her art has a lot to offer thoughtful animators as well as story artists.

A frame from the film "Daddy Long Legs"; Mary is playing a 12 year old here, in the first half of the film. A wealthy girl has just called Mary a bastard, literally,and she turns to give this glare

A frame from the film "Daddy Long Legs"; Mary is playing a 12 year old here, in the first half of the film. A wealthy girl has just called Mary a bastard, literally,and she turns to give this glareMary Pickford is best known today as an actress in silent movies who played adorable little girls with long blond ringlets, but that's a terribly superficial description that does her talent and charm no favors. As a kid I was vaguely aware of her in much the same way as I was Chaplin and Keaton: quaint, black and white images in books--and virtually nothing more. Her films were nowhere--she was still alive back then, owned most of them, and didn't want them to be seen. She was a famously reclusive frail little old lady tucked away in her mansion in Beverly Hills, "Pickfair". She formed her own film company and later founded United Artists Corporation with Chaplin, D.W. Griffith, and her husband Douglas Fairbanks. Along the way she also helped found the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to honor screen achievement with "Academy awards"; started the Motion Picture Fund, including the "home"--a beautiful retirement community for the benefit of anyone who'd contributed to work in filmmaking(in pre-union days, remember), and contributed mightily to other charities.

As a kid I came across a biography of her which I bought based mainly on the cover photograph: Mary in a pretty pose surrounded by puppies(she looked young, like an illustration--or a living doll; of no determinate age; she was probably really about 28). It

was a beautiful, painterly, victorian image, and the biography had some interesting stories of Mary becoming famous back in the 1910s. Years went by and I gathered bits of information about her--winced at her disturbing acceptance of an honorary Oscar on TV, went to screenings at the Academy that she helped to found, read of her death and the subsequent fire sale of all her possessions from Pickfair...but still, I'd never seen more than a few tiny clips of her

on film, in Kevin Brownlow's terrific television series on silent films, "Hollywood: The Pioneers". But there was little of Pickford to see other than some 16mm D. W. Griffith prints at the Silent Movie Theatre on Fairfax, dating from 1910 or so. Interesting, but hard to watch.

Finally, about 6 years ago the Academy presented a restored print of a 1919 Pickford film, "The Hoodlum". By the way--If you ever have a chance to see

any film projected at the Academy, go. They do public screenings of all sorts of films regularly, usually charging all of five bucks.

Watching "The Hoodlum" in a beautifully restored print with an audience on the big screen was a revelation.

Made in 1919, it was exquisitely photographed, funny and touching by turns--and featured a charismatic star at her peak. I had also bought the concurrent book "Mary Pickford Rediscovered", a coffee table volume that in and of itself offers gorgeous images, including many scene stills that make one yearn to see the films they are from. It all combined made me an instant Pickford fan.

The title I saw the other night, "Behind the Scenes", was from a year that sounds incredibly long ago: 1914. Think for a moment where animated cartoons were at that point in cinema history--even Krazy Kat hadn't been animated yet. There was J.R.Bray, Winsor McCay, and some others...but most of it (with the notable exception of McCay's singular work) was terribly crude stuff.

Not so the live action features, at least the ones like "Behind the Scenes" which had a very involved star player like Pickford in front of the camera and were "A" productions. Not every film she made during this time was a gem (personally I have trouble making it through "Cinderella", also from 1914), but it's easy to see at this early point why she was a huge sensation.

As I wrote before, she also has I think great things of interest to animation artists in her acting. She even

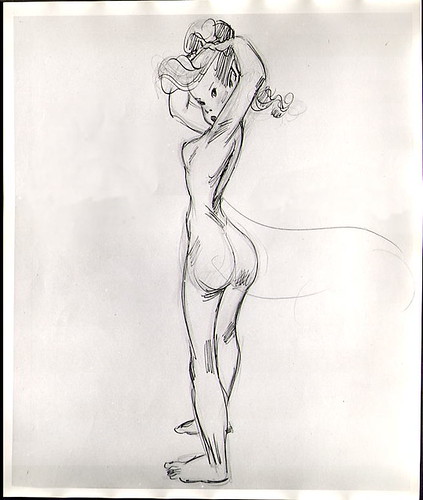

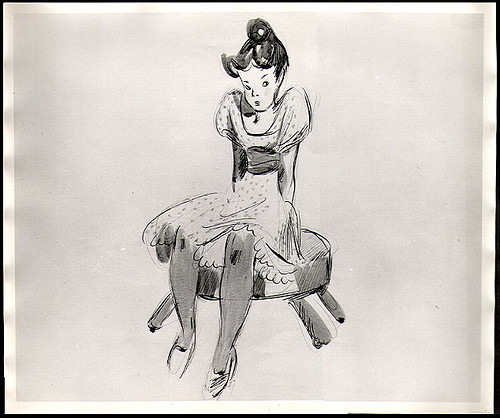

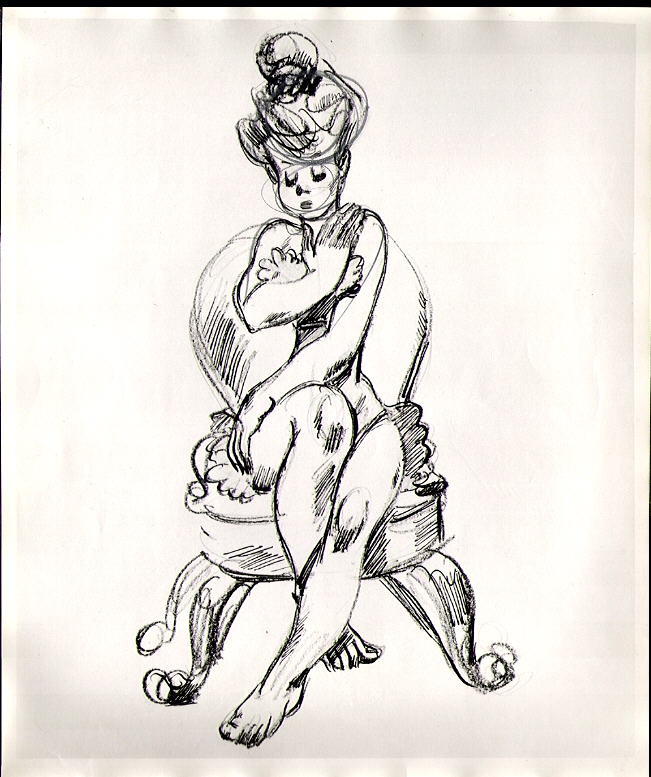

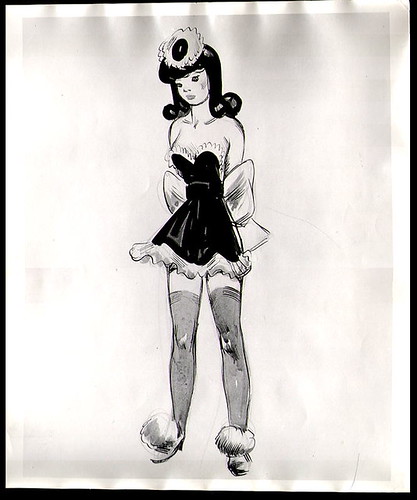

resembles an animated character, albeit one of the most sophisticated type. Her familiar "little girl" persona manages to be emblematic of girlhood or childhood without becoming a pastiche. She does this by a sensitive, economical study of movement and pantomime, and by dint of possessing a peculiarly unclassifiable face. She's young, wise, serious and puckish. Small in stature, with a short waist and a large head(cartoon proportions!) she uses her size to her advantage, managing to pull herself up till she seems very "big" on the screen. She uses her small, elegant hands sparingly, never moving them to no purpose, so when they do move they attract attention naturally. She makes herself endlessly malleable for the camera, but never seems self-conscious as some silent era actors do.

In "Behind the Scenes" she plays a young woman her own age(about 22); an actress on the neo-vaudeville stage, appearing in a "Follies" sort of entertainment. She fools around in the communal dressing room with her pals, the other actresses, and her timing and sheer enjoyment of everything she's doing bubbles over onto the celluloid.

A young man trying to make it in NYC visits the theatre with a wealthy school friend, and Pickford meets him after throwing a balled-up streamer directly into his eye from the stage. This part is played by the film's director, James Kirkwood. He's very tall, very attractive and just oozes masculinity (he and his star Pickford were thought to have carried on an intense affair offscreen; rumors like that are a dime a dozen but watching them working together in this film it's utterly believable). He marries the young chorus girl, and they live in crummy digs while she continues the stage work she loves. After he comes into money requiring him to take over a rural farm, he naturally (for the times) expects her to drop everything in New York and move with him. They're deeply in love, and one oddly-staged scene makes clear that she loves babies and wants a family with her husband, eventually.

But Mary is crushed to learn her husband thinks nothing of asking her to abruptly dump her career--especially as she's finally,

finally gotten a chance at the lead role. She balks at moving from New York to a farm in the middle of nowhere with nothing to do but housekeeping. For 1914, this is pretty wild stuff, but it's handled from Mary's point of view, not her husband's--even more astonishing for the times.

This is where Mary Pickford's special qualities really shine. She's been as charming as a young heroine could be up till this point in the film: graceful, endearing and playful, always upbeat. Now, suddenly she discovers her life--everything it means to her apart from her new husband--is over, and she's expected to leave every vestige of it behind her for--what, she's not sure. I can't describe the looks that cross Pickford's face as she realizes this; they're

so real, so believable, that when she speaks (there are almost no "title cards" translating her and her husband's dialogue for us) we can hear exactly what she's saying: "But...what will I

do on a farm? What about my job at the theatre?" Her gestures are economical--there's no wringing of hands or meaningless posing--it's all very natural and felt. She described herself as a "mood actor" to Kevin Brownlow, and she was. The plot unfolds in a surprising way-she leaves her husband, in a sustained scene that starts off with Mary finally uncorking the frustration and grief she feels. Of course, all ends well, but not until she's had her chance to go back "behind the scenes"--the original, literal meaning of the phrase: to stand behind the painted sets, waiting for a cue.

Afterwards, my friend commented that the film was so-so, nothing special--but he thought

Mary was sensational in it. It's more or less true; I was entertained all the way through it, but it really needed the boost of a one of a kind star presence, which it certainly had in Pickford. Her ability to make something out a very simple story and what could have been a stock ingenue character were what made her the most famous and adored actress in the world at that time, and for about a decade. She had a large amount of control over her films, from her performance to the writers to the director, photographer and the rest of the cast. She was determined to try different things, many of which didn't work, but she was always striving for a sincere performance in an entertaining film. I think she would have loved the animation production process, with the opportunities it offers for total control of every aspect of a movie. And I suspect the problem of delivering a great animation performance via drawings would have fascinated her too.

Of particular interest to animators is that while Pickford and the cast performed these scenes there was live music on the set to help them achieve the proper mood. This was done during single, non-dialogue shots of Mary walking around her home, closeups of her thinking...if ever there was a shared intuition and methodology between artists, it would be this sort of actress and an animator who also draws to beats, and animates characters with the same rhythm and timing--timing of movement lost to any sort of acting but the ballet today, with a few exceptions.

I've grabbed a few frames directly from the film "Daddy Long Legs"(1919).

What I realize after removing them is how much they need the frames all around them to have the impact they do(well, that's film for you)--but I've left them here anyway; hopefully they offer some idea of her visual charm. One of the great things that distinguished Pickford from other pretty faces of the period is what always elevates actors: the magical glimpse of thought fleeting across her face; sincere, real, totally believable thought. It's a crucial element for animation, obviously. Even in broad comedy, if the characters in a feature lose believability, they can't sustain the kind of humor I think is the best kind for our medium: character-based, idiosyncratic, relatable humor.

Bear with me as once again I cite "The Incredibles"--for the very good reason that

it's always on one or more of my cable channels, and I have one particular scene stuck in my mind while writing this:

Watching superhero coture designer Edna Mode walk across her inner sanctum is

funny movement. Her tiny legs switch back and forth like a beetle's while her huge head stays almost entirely still by comparison. I don't laugh out loud at it, but it's a perfect, amusing bit of character. But her gestures and the expression in her eyes in her ensuing dialogue: [paraphrasing here]"Men of Robert's age are unstaAable and prrrone to weaknessssss"--

that's really funny to me. It comes straight out of the character and could

only be said by THAT character in that situation. It's specific character-based humor, even though the scene isn't meant to be a total laughfest but more a contrapuntal blend of plot advancement, drama and humor.

I'm sure it's no accident that Brad Bird has been going to screenings of old movies as long as he has--going back over 20 years. There's a lot there that anyone can learn from and that can help us make the kinds of entertainment we hope will last.

In the book

Mary Pickford Rediscovered, Kevin Brownlow writes of a rare interview he had with the great pioneer, Pickford, then 72. She tells him: "Imagine that of all the children I have, Kevin, none of them have used my experience. To me, that is for me to die". It's very sad, and at the time (1964) it must have seemed true to her in many ways. Of course by "children" she meant all those who came after her in the filmmaking world, and by her "experience" she meant exactly that: the discovery by trial and error she participated in of what would work on the screen as a story. Even she felt her films should be destroyed, as she'd seen how the media derided silent movies, the horrible prints shown at the wrong, too-fast speed making them look ridiculous, the emphasis on the "corny" old-fashioned stories while ignoring the existence of astonishing, adult and gorgeously mounted films that made the early talkies look as stilted and crude as they were. Now on DVD and at screenings such as the Academy's and MOMA's a new generation can appreciate the craftsmanship that was all over these best films of the era and marvel at the fact that much of the technique was being done

for the very first time. And again, lots for animation folk to learn from. If Pickford isn't your thing, there's Keaton, DeMille, Gish, Chaney(the Tod Browning-Lon Chaney collaborations still haven't been matched for shocks), dozens of others. Pick up a copy of

"The Parade's Gone By", and see if it doesn't whet your appetite.

By the way, I'm not the only crossover person from animation who was there the other night; I finally met a sort of author hero of mine, Joe Adamson(our mutual friend Mike Hawks introduced us). I owe him a huge debt just for writing "Tex Avery: King of Cartoons"(published when there was literally not a single thing available on the WB directors), "The Walter Lantz Story", and especially, "Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Sometimes Zeppo", a book on the Marx Bros and their films that had me laughing myself out of bed at 2am many many nights during my high school years(and afterwards).

By the way, I'm not the only crossover person from animation who was there the other night; I finally met a sort of author hero of mine, Joe Adamson(our mutual friend Mike Hawks introduced us). I owe him a huge debt just for writing "Tex Avery: King of Cartoons"(published when there was literally not a single thing available on the WB directors), "The Walter Lantz Story", and especially, "Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Sometimes Zeppo", a book on the Marx Bros and their films that had me laughing myself out of bed at 2am many many nights during my high school years(and afterwards).