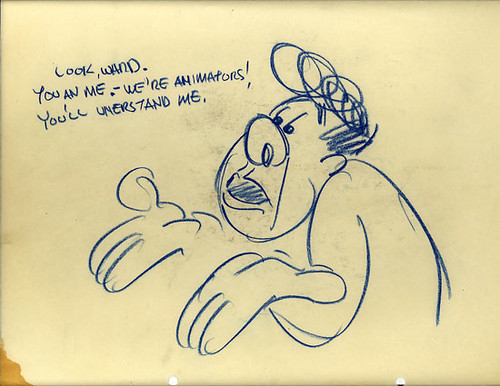

Fred Moore's Lampwick, from "Pinochio". A likeable bad guy.

Fred Moore's Lampwick, from "Pinochio". A likeable bad guy.A long time ago at a studio a few miles away, there once was a script that I and a half dozen others storyboarded. The main character was a little guy, meant to be cute, who was also presented as a tremendous pain in the ass. Really. That was intentional; the entire plot demanded that he hate everything about his warm, comfortable, upper-class life and want to go out and "see the world". He wasn't micromanaged like the famous clownfish Nemo, he only had the most basic kinds of parental attention and discipline to deal with--but for the purposes of the story he just plain hated...everything.

Now, I had a few problems with this.

First, I didn't see any reason given why this adolescent animal character would have developed a distaste for the things I see

my pets crave: affection, interaction with their pals (both animal and human), warmth, shelter, and especially

food. It still might have been possible to make a better case for wanderlust, if it had been

shown rather than stated: "I want adventure!".

But the main problem was a very obvious and basic one: the character as presented in the story was unlikeable. He was selfish, rude--and selfishly rude, and a dozen other tiresome variations on selfish and rude. Apparently it was more important to the writers that we follow the adventures of a truly unpleasant character, supposedly identifying with him for 80 minutes, just so his story arc could have him redeemed at the end.

I don't know about you, but when I watch an animated film, especially one with rich potential for fun and high spirits and comedy, I don't want to be forced to either sit through a therapy session with a mediocre analyst, nor do I want to spend most of that time with a jerk. That doesn't mean that a character has to be perfect, or perfectly happy, or have no troubles. But there's been a trend in all types of film to insist that the character can't just

face a conflict, he or she has to be terribly flawed and conflicted

himself. It used to denote depth in a character. It's become a formula and it's an approach that needs to be handled with incredible finesse to work. Think that happens regularly?

It

can work: "The Incredibles" is filled with scenes that usually make me check my watch or wish I had brought a penlight and a book, or earplugs: a screaming family argument at the dinner table; a brother and sister snarking and screaming at each other; more nagging and/or arguing between the parents...everyone knows those scenes. Millions of people, in fact. The difference--and it's crucial--is that the characters were introduced with great delicacy, with humor, with humanity. We

liked them--a lot. So that by the time they begin to break down, instead of a turn off, the drama is really that--dramatic. I, who hate typical movie argument scenes, happened to turn on HBO the other night; "Incredibles" was on, in the middle of the "total chaos" dinner scene. Instead of turning it off(and even though I've seen it numerous times)I found myself sitting down and enjoying it again--for the timing, the performances, the master juggling act of the director/writer, animators and art direction, the

story--the whole enchilada. Great and honest filmmaking, with real characters. All

animated. You can't look away!

Another film where the use of sometimes unpleasant characters works, almost invisibly, is "Lilo & Stitch". There we really have what might be described as a disturbed kid. A disturbed, unhappy, occasionally downright bratty

animated kid--usually the kind of thing that spells nails on a blackboard for me. But though it sometimes seems like it might tip over, it never does descend into the Land Of No Return for Lilo. I think it's because that while she acts up, throws tantrums, is just terribly awful to her poor sister(who really is trying), she also clearly doesn't want to be a brat. She loves life, is filled with energy and imagination and is always trying to invent her own better world--which makes for the entertainment, the pathos and the comedy of her Elvis adoration, her photograph collection, her always-hatching plans for Stitch, whether he agrees or not. She's an inexorable, contradictory force of nature--in other words, a bit of a real little girl. A rare thing to find in the last 15 years of animation, unfortunately.

Show the audience "real" in some form and you

will win their sympathy(and it won't matter a damn how extreme the characters look, either; they could be as designy as a MOMA exhibit, so to speak). Construct characters whose actions are dictated by plot demands and neuroses that presumably give them something to "change" from or shuck off unconvincingly in Act 3 and the unreality tells.

Story artists get very close to their characters. As I've written before, whatever the situation, when we have a scene we've got to work out, depending upon the amount of freedom in the scene to add or improvise, it's almost impossible not to

become the characters and once you've taken them on, to find that they surprise you with bits of business or a new idea that you didn't have when you started. That's a good thing.

If, however, you start with a character who's motivation is indecipherable or who you just plain don't like... The scene has to be done in any case, but where feeling is lacking--through no fault of the artist--it shows. In the best of times those scenes get tossed out; it becomes evident that there's a lack of sympathy there and your audience at work is expected to be frank. But often these roadblocks could be avoided if the essence of the character--if

his "character"--weren't forced into an off-putting attitude at the story's conception. These are really important things to consider. It may seem a fine line between a character who

has a problem and one who

is a problem, but the line is there and once crossed it results in a disconnect that takes a hell of a lot of work to fix.

Starting out with good, likeable protagonists isn't hard; we make our own casting decisions every day--and art imitates life. Who would you rather have lunch with: the person who sits down already griping and irritable, totally self-absorbed and uninterested in you, or the one who smiles, is glad to see you, maybe cracks a joke and asks how you're doing

before settling down to griping about the lousy job the mechanic did on his car yesterday? That second guy will have you with him all the way, won't he? The first one? You'd be checked out by the time he gets around to telling you why he's so dissatisfied with his life. Characters can have struggles and problems and hey--quirks! But leaven them with the things we respond to in our friends, in the person that attacts us on the train with their smiling face or the bizarre choice in reading material they're holding that suggests a totally different inner life. Whatever. It

is possible to come up with layered characters for animation. In fact, it's easier to do than to struggle with guys who have something they have to "do" but no real reason why the audience should be watching

them do it.

Just so you know we

do think about these things.

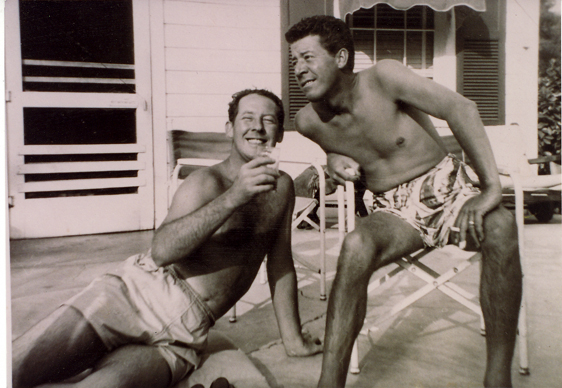

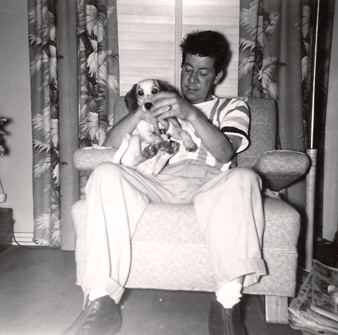

. God, what a painter and caricaturist! Also just the kindest man you could find. Very lucky I am to be around such guys.

. God, what a painter and caricaturist! Also just the kindest man you could find. Very lucky I am to be around such guys.