The title of this entry has quotes around it because it's an old, old aphorism.

[aph·o·rism [af-uh-riz-uhm]: a terse saying embodying a general truth, or astute observation, as “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely”]

A cursory scan of a few reviews of a certain just-released animated film forced me to the laptop for this brief post. One of the more positive ones is sub-headlined, "Though impressive, the 3-D retro-futurist look and time-travel plot feel almost old-fashioned."

The first thing I think--instantly--is, "what exactly is "wrong" with "old-fashioned"? The reviewer is apparently implying that certain large elements are tired, been-there, seen-that--but when those elements are a lonely boy, or a beautifully-moderne design of the future...what the heck? I'm sincerely baffled with the problem.

See, as far as I can tell, every element of storytelling was "done" by the time those cave paintings were drying in France.

My previous post was a nod to a film from 1959, an "old" movie--a black and white movie, for heaven's sake--and moreover a film that was set in the jazz age of gangsters and flappers...old-fashioned stuff even then, 50 years ago. Describe any of the plot contrivances and see if someone doesn't say "but they did that in The Untouchables/Road To Perdition/Gloria/The Professional!" It neither takes away from or diminshes any of the subsequent movies that they share situations and themes. And I'm not even adressing the drag aspect.

Anyway, I haven't yet seen the film in question. In a few hours I will have. I'm looking forward to it.

But not having seen it, I can't defend anyone's take one way or the other. What I can do is protest the lazy fallback of too many film writers vis a vis animation these day--these reviews where the reviewer is bored to tears not because the movie is slow, or lousy, or stupid, or poorly-done(in fact, I've noticed that increasingly animation's artistry is virtually--gah! no pun intended --ignored as almost irrelevant...and when it is criticized, it's done from what often seems a very uninformed observer).

No, the reviewer is bored, or jaded, and why? A sighing plaint of "but...this is all so old fashioned. We've seen orphans before(really? Where lately?), singing frogs before (as if the existence of the short "One Froggy Evening" meant that 60 years later a filmmaker is risking ridicule if he uses a frog in an animated film, no matter the context? You've got to be kidding--yet a writer made just that beef in his review)".

And to them I say, well, [see post below]: did any of the characters come alive for you? Did you settle down and believe in any of it for any amount of time? Were you entertained, or is this all an intellectual reporter's excercise in animation overload?

There's no percentage in arguing reviews, none. But I do mind, and am bothered, when the reviews seem so disconnected from the actual film itself, and more a general indictment of my profession.

It's unfair and anti-film to look at ANY film and review it as if it owes its impact to any other film. This is where I guess a writer has to pretend as hard as he or she can that they haven't seen every. single. film. released in the last 10 years, and compare them to one another. Because each is made to be seen for the first time, and especially in the case of family audiences, many of the viewers will have seen none of the preceding movies that a new one is "too much like". When they do each and every individual film will stand--or fall--on its own merits.

And personally I suspect good movies are good not because everything in them is new! but because the things in them are old: warmth, humor, wit, friendship, awe, drama.

I hope this little screed makes some sense.

animated cartoons are made by artists. whatever the method the goal is the same: the illusion of life

Mar 28, 2007

Some Like It Hot -Running Wild

I apologize for posting such a lengthy clip-the scene I had on my mind is a couple of minutes in, and until someone gives me a tutorial in excerpting my own DVDs to youtube this'll have to do.

What hasn't already been said of "Some Like It Hot"? Brilliant film; great director, great script, great cast. Take the little musical interlude of Sweet Sue's blondes rehearsing "Running Wild": what particularly strikes me is how such a simple scene manages to be so infectious and feel so totally uncontrived--even though Jack Lemmon is playing a dead ringer for Daffy Duck and Tony Curtis is in the most grotesque drag since...well, perhaps ever.

Even with all the broad, Wilderian goofiness they seem real. They genuinely enjoy their jazz playing, "Sugar"(Marilyn)has a ball shaking the lead vocal and strumming her ukelele, and it all results in making you feel like you're not only sharing the ride on a Florida-bound train in the 1920s, you are a part of the relationship between the characters, however improbable they are.

If there's one thing that doesn't get enough attention in many animated films it's the character relationships. It doesn't matter how they're related--whether on the surface the relationship is what we'd call conventional--what matters is that we really buy that these characters believe in each other. I don't mean "believe in" in a sentimental "I have faith in you" way (not that there's anything wrong with that-that certainly has its place in the right narrative), but rather that one character clearly knows and has real feelings towards another.

This sounds pretty elementary--a no-brainer--but oftimes in the midst of getting the plot moving along, throwing in a gag here or there(or taking one out), and making the nominal plot exciting or whatever the characters can lose their realness. I'm sure everyone has expereinced the sinking feeling in a theater when you disconnect from the characters...and then the action on the screen; the next step is checking your watch and after that--planning where you're going for dinner. Uh-oh.

"Some Like it Hot" has some ludicrous characters in silly, totally implausible situations--but we're with Joe and Jerry all the way. They argue, laugh, get furious and concerned with each other as believably as if they were in an Elia Kazan film, not a farce by Wilder and Diamond....but then, all of Wilder's best films manage to sell some pretty messed-up plots and seriously compromised characters by making the audience empathise with them, like them ,and just plain buy them.

it's been argued that animation filmmakers have their work cut out for them in the casting department: we can't rely on the human face to carry a scene, or the comes-equipped charm of an actress or actor to fill in the subtext; we have to build a real person(or animal)from scratch. But surely Wilder and Diamond had the same problem here: two goofball, skirt-chasing jazz age musician losers, dressed as women for the majority of the film, affecting silly voices and enduring ridiculous circumstances. I think the glue that holds their characters together--including Monroe's--are very clever and suprisingly subtle touches that add up to people we can relate to and believe in. The St. Valentine's Day massacre scene isn't played for laughs in this oh-so-broad comedy, and Lemmon's delivery of the line "I think I'm gonna be sick" after witnessing murder is as straight as if it were part of a hard core film noir. Monroe's Sugar has real poignancy along with her burlesque-style blonde goofiness...again, very careful nurturing of characters.

The film has so much bizarre action, broad characters and great lines that the characters might be presented a fraction as well and everyone would still laugh...but the way it turned out results in a flm that can be watched over and over again without too much fatigue. There's no reason the same can't be true of animated actors.

Mar 22, 2007

In a story, it's the little things that count-a sort of manifesto

If anything from my experience of the last 15 years or so has made itself clear to me as a story truism, it's that the importance of the smallest details matter.

It's that the difference between a dull scene or a stock character and one that breathes, that thinks, is in the details. Details spring out and suggest themselves when the story artist believes in a character's reality no matter how superficially unlikely the scenario they're placed in might be.

There are times when a story artist is given a sequence that's already laid out pretty extensively: the characters must say this or that, do this, that and the other thing, get from here to there. Now, you might think that that would be a boring sort of sequence to work on--not necessarily.

Of course one wants to be as creative as one can, but in putting a feature film together there's not always an opportunity to start from scratch(and if there always is, the film's probably in trouble). Does that mean there's no room for the story guy to have fun, to make an impression, to enhance or "create" the scene? Far from it. But you'd better believe in the characters you're working with.

If you do, wonderful things can happen. Some of it might wander off in a direction that will result in the kibosh being put on the sequence in whole or in part--a great big old redo. But sometimes (often enough of you're both lucky and inspired)a sudden, truthful idea will pop up seemingly out of nowhere and work so well it's just got to go in. No one planned for it until it struck--you didn't see it until you were least expecting it, surrounded at your desk by crumpled paper and worn down stubs. Suddenly it's there, and it seems exactly the thing the character should say or do at that moment. If it really is as right as it feels, it'll make it into the film. You'd be surprised how often that happens, in spite of any and all obstacles.

This to me is the most exciting, rewarding part of my job, but it's not a daily occurance--it couldn't be. Films just don't play with too much going on at every second, all the time. They flow in a narrative dance in any of a million permutations, all with one commonly understood goal: to tell you a story.

And I should mention that the function of your storyboards is twofold: not only are you designing the action withon the frame, but most importantly you're responsible for setting the mood and emotion of the scene--that's how it's supposed to be, anyway. This really can't be stressed too strongly. The times that a completely flat, emotionless story sequence didn't work in boards but came to life in animation, out of nowhere is exactly zero. Can sequences be plussed by animation? You bet, and they almost always are--hugely. The medium is about moving drawings/characters, after all. But plussing has to start from something. The drawings needn't necessarily be fancy, but they must certainly read, and communicate. The more direct and meaningful the better. Otherwise the animator really is left with nothing to work with.

We in animation have a big hurdle, a doozy: we have to take a two-dimensional, stylized design of a character and entice the audience into caring about it. I believe the key to doing that is to lend the characters your faith while you board them--to invest them with little parts of your life in the form of those little details.

All of this comes from you, from your own real personal experience and your unique observation. To have to squeeze the wonky story-peg into a predetermined hole doesn't always work--often these characters take over, just a bit. Or a bit more than a bit. To know when and how to apply your observation and build each character a soul--that's where your day to day story experience hopefully takes you.

It's why I do this job, why I love it; it's like climbing a mountain that grows as I grow. The mountain is impossibly huge but it can be conquered at the most unpredictable times, if you keep your imagination open and remember to find truth and realness in the little details of life.

It's that the difference between a dull scene or a stock character and one that breathes, that thinks, is in the details. Details spring out and suggest themselves when the story artist believes in a character's reality no matter how superficially unlikely the scenario they're placed in might be.

There are times when a story artist is given a sequence that's already laid out pretty extensively: the characters must say this or that, do this, that and the other thing, get from here to there. Now, you might think that that would be a boring sort of sequence to work on--not necessarily.

Of course one wants to be as creative as one can, but in putting a feature film together there's not always an opportunity to start from scratch(and if there always is, the film's probably in trouble). Does that mean there's no room for the story guy to have fun, to make an impression, to enhance or "create" the scene? Far from it. But you'd better believe in the characters you're working with.

If you do, wonderful things can happen. Some of it might wander off in a direction that will result in the kibosh being put on the sequence in whole or in part--a great big old redo. But sometimes (often enough of you're both lucky and inspired)a sudden, truthful idea will pop up seemingly out of nowhere and work so well it's just got to go in. No one planned for it until it struck--you didn't see it until you were least expecting it, surrounded at your desk by crumpled paper and worn down stubs. Suddenly it's there, and it seems exactly the thing the character should say or do at that moment. If it really is as right as it feels, it'll make it into the film. You'd be surprised how often that happens, in spite of any and all obstacles.

This to me is the most exciting, rewarding part of my job, but it's not a daily occurance--it couldn't be. Films just don't play with too much going on at every second, all the time. They flow in a narrative dance in any of a million permutations, all with one commonly understood goal: to tell you a story.

And I should mention that the function of your storyboards is twofold: not only are you designing the action withon the frame, but most importantly you're responsible for setting the mood and emotion of the scene--that's how it's supposed to be, anyway. This really can't be stressed too strongly. The times that a completely flat, emotionless story sequence didn't work in boards but came to life in animation, out of nowhere is exactly zero. Can sequences be plussed by animation? You bet, and they almost always are--hugely. The medium is about moving drawings/characters, after all. But plussing has to start from something. The drawings needn't necessarily be fancy, but they must certainly read, and communicate. The more direct and meaningful the better. Otherwise the animator really is left with nothing to work with.

We in animation have a big hurdle, a doozy: we have to take a two-dimensional, stylized design of a character and entice the audience into caring about it. I believe the key to doing that is to lend the characters your faith while you board them--to invest them with little parts of your life in the form of those little details.

All of this comes from you, from your own real personal experience and your unique observation. To have to squeeze the wonky story-peg into a predetermined hole doesn't always work--often these characters take over, just a bit. Or a bit more than a bit. To know when and how to apply your observation and build each character a soul--that's where your day to day story experience hopefully takes you.

It's why I do this job, why I love it; it's like climbing a mountain that grows as I grow. The mountain is impossibly huge but it can be conquered at the most unpredictable times, if you keep your imagination open and remember to find truth and realness in the little details of life.

Mar 21, 2007

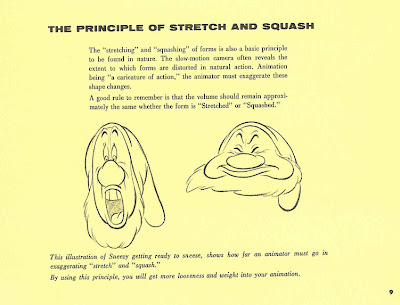

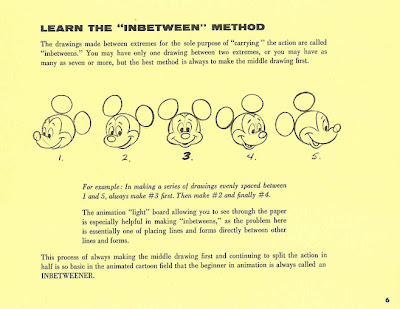

Tips on Animation, part 2

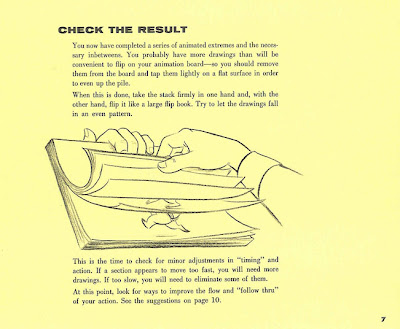

Courtesy of Dan Jenkins genrosity, here's the rest of the booklet "Tips on Animation". It's actually a very sober, accurate, solidly composed basic animation guide--again, I wish it had been available when I was growing up. There's no "talking down" here, even though the target audience is one of kids. And who can't love the offer to (for an unspecified fee) actually shoot the juior animators' tests, and return them?

Mar 20, 2007

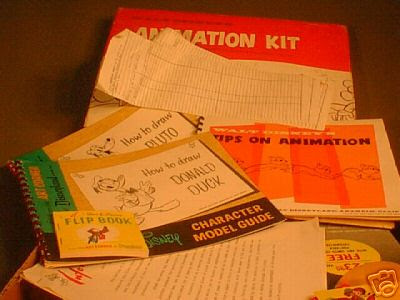

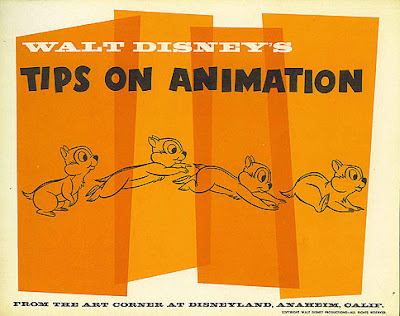

Disney's Tips on Animation, part 1

the Disney Animation Kit--an Ebay item I unfortunately didn't win about a month ago: this example shows what a swell item it really was for kids wanting to try their hand at the art of animation. The question is--why didn't Disney keep this sort of thing available for the next 30 years? I would have killed for one myself, but by the time I was old enough to read they were long gone.

Dan Jenkins, a reader of the Diaries and a serious collector of cool Disney items, has offered to share scans of the rest of the series of booklets that were sold both in the Disneyland's Art Corner in the early 1960s and as part of an incredibly cool "animation kit" that from the looks of this wasn't half bad. Herewith is the first of a series of posts of these fun "How to" books, "Tips On Animation"--and thanks, Dan!

Remember to click the images to open them in a larger window. More to follow.

Mar 17, 2007

Vorkapich-pure genius, never dated

Slavko Vorkapich was a genius of film, little known today although he personally contributed to incredible sequences in many Hollywood films of the 1930s. The first I ever saw was a hallucinogenic dream sequence he designed for the Claude Rains film "Crime Without Passion" which has to be seen to be believed; if my memory's correct, it probably helped inspire some of the more bizarre imagery in Fantasia's Bald Mountain sequence. Vorkapich was practically unique in his freelancing just montages for so many large scale films for different studios-which gives an indication that the studio bosses knew greatness when they saw it.

The clip here is of course of Vorkapich's visualization of the Great 1906 earthquake in MGM's "San Francisco", directed in all but this montage by W.S, Van Dyke("The Thin Man", among many others). The rest of the film is fairly straightforward romantic drama with Clark Gable at his staccato angriest, tempted as he is to decency by lovely Jeanette MacDonald. Spencer Tracy plays his usual tough Irish priest, friend to both the leads. But all the melodramatic twists of the plot pale next to this incredible, impressionistic, utterly jaw-dropping piece of cinema that represents a staggering disaster--made in 1936.

See how the tension in the conventional plot builds with Gable's public embarrassment of Jeanette, and how a few disturbing quick cuts to the audience members create a sense of unease and disturbance(probably Van Dyke's)...then as Jeanette walks through the crowd the familiar rumble of the earthquake starts, resulting in the actress stopping abruptly and turning back with a muffled, panicked "What's that?"--so clipped it almost sounds like an ad lib(it surely wasn't). Then here we go...

There's no music. The shots are seemingly erratic: the ceiling, the slivers of plaster, the glasses, the roar of the earthquake, the screaming starting...the sound building to the wheel falling--and then a second or two of pure silence.

It's still got every bit of its impact today. The only pity is that this is humble YouTube quality, and doesn't do it full justice. But what a lesson in editing for impact. I think we have a lot to learn from this.

There's one little historic inaccuracy: the actual earthquake struck at 5:15 am, not many hour earlier as the film's plot indicates, but that's a small caveat. Everything else shown is based on a reality that was--hard to imagine--only thirty years in the past at the time this was made.

Mar 14, 2007

Working on it

from my sketchblog. I've got to put something visual up, for pete's sake.

Simply because I myself get antsy when a blog doesn't update I thought I'd enter a little placeholder of a post to say that I'm currently in the process of writing a couple of things. There's a lot going on at work--even more than usual-- and a full plate outside of work, precluding much writing time. In the meanwhile I'm really enjoying zipping around having a good look at what everyone else is updating. There's an unbelievable amount of great stuff going up lately--especially personal artwork. If you haven't clicked through the links here lately, I urge you to do so--it's a long list but every one is a treat.

I did recently pull out my old facsimile copy of "The Mousetrap", a privately published...well, it's a kind of zine of the 1940s(very early 40s, I think--I believe the date is in the book). Contributors to this onetime magazine/book included Ward Kimball and Fred Moore--Moore's drawings from this publication(there are several pages of them) have been reproduced many places at various times, but as these copies are so good-looking I thought I'd scan them for inclusion here.

So that's one thing.

I've also been promised scans of the other "How To Draw" books that Disneyland sold in the 1950s: Chip and Dale, Mickey, and Donald among them. I'll be sure to put those up as soon as I received them--it's a lot of work for the owner to do, and he's been very generous to offer to share them here.

More soon, then. Happy midweek, everyone.

Mar 8, 2007

Calarts au courant: Lorelay Bove and Leo Matsuda

My friend Dave was waxing proudly on his class at Calarts.

He teaches story to second years, frequently asking friends and colleagues to come to Valencia to speak and offer the students some feedback.

Last night the guests were Shannon Tindle and Shane Prigmore, two artists Dreamworks is fortunate to have. Definitely visit their respective blogs.

And speaking of blogs, Dave introduced me to two current Calarts students you should know:

Spain's Lorelay Bove

And from Brazil, Leo Matsuda.

Both of these young artists have blogs filled with juicy eye candy. It's wonderful to think that they're at the very start of their careers. Heaven only knows who else is out there that we generally don't know about or stumble across in the blogosphere--that's what makes it especially fun to see the work of brand new talent. Great stuff, guys.

He teaches story to second years, frequently asking friends and colleagues to come to Valencia to speak and offer the students some feedback.

Last night the guests were Shannon Tindle and Shane Prigmore, two artists Dreamworks is fortunate to have. Definitely visit their respective blogs.

And speaking of blogs, Dave introduced me to two current Calarts students you should know:

Spain's Lorelay Bove

And from Brazil, Leo Matsuda.

Both of these young artists have blogs filled with juicy eye candy. It's wonderful to think that they're at the very start of their careers. Heaven only knows who else is out there that we generally don't know about or stumble across in the blogosphere--that's what makes it especially fun to see the work of brand new talent. Great stuff, guys.