"It’s Not a Sequel, but It Might Seem Like One After the Ads"

By Michael Cieply

LOS ANGELES, April 23 — If the Walt Disney Company and its Pixar Animation Studios unit have their way, by the time “Ratatouille” is released on June 29, millions will have learned not only to pronounce the movie’s title — Pixar’s Web site insists on the somewhat un-French “rat-a-too-ee” — but to love the idea of a rodent in the kitchen.

But not without some extraordinary effort. Next Tuesday, Disney will unleash an unusual all-day television advertising campaign, culminating with a 90-second spot on “American Idol,” intended to drive viewers to a nine-and-a-half-minute clip from the film at disney.com.

In effect, the studio is promoting its promotion.

Such bravura is necessary in this case because Disney and Pixar have once again staked their fortunes on a big-budget film that is completely original in concept and execution at a time when ticket buyers have shown a growing preference for repeat performances of known commodities like “Spider-Man,” “Shrek” and Disney’s own “Pirates of the Caribbean.”

“It takes a lot more work,” Richard Cook, chairman of Walt Disney Studios, said of the effort to introduce original films. “The rewards can be unbelievable. But they’re clearly more difficult to market.”

That originality is a dying value on the blockbuster end of the movie business is no secret. In the last five years, only about 20 percent of the films with more than $200 million in domestic ticket sales were purely original in concept, rather than a sequel or an adaptation of some pre-existing material like “The Da Vinci Code.”

In the 1990s, originals accounted for more than twice that share, led by “Titanic,” which took in more than $600 million at the box office after its release in 1997.

Pixar and Disney have enviable name recognition among moviegoers compared with virtually any other studio. But when an original like “Ratatouille” costs roughly $100 million to make and perhaps half that to market in the United States alone, even they cannot trust viewers to show up without a painstaking introduction.

“Wonder takes time,” said Brad Bird, the movie’s director. “You don’t rush wonder. You have to coax the audience toward you a little bit.”

Born of an idea from the animator Jan Pinkava (“A Bug’s Life”) and others, “Ratatouille” is not only original but also a bit subtler than some of its Pixar predecessors. Without superheroes, as in Mr. Bird’s “Incredibles,” or talking toys, as in the “Toy Story” films, it is about a rat who wants to cook in a French restaurant that once had five stars, but has slipped a couple of notches.

The conceit brings with it something of an “ick” factor, Mr. Bird acknowledged. Yet he resisted calls during production to make the lead character, Remy, more human and less ratlike. And he predicted that even the whiff of aversion would become an asset in seeking attention in a crowded season.

“That ‘ick’ is something in our favor,” he said. “It makes the story more interesting.”

(Disney, for its part, has generally done well with rodents, from Mickey and Minnie Mouse through the creatures in “Cinderella” and the “Rescuers” films.)

“Ratatouille” has already appeared in a trailer, attached to “Cars” almost a year ago. And Mr. Bird helped produce an elaborate promotional video that circulated on the Web this spring, even as he scrambled to finish the film, which he took over two years ago from its original director, Mr. Pinkava.

As the release date nears, Disney will add ploys like a scratch-and-sniff book from Random House (“I Smell a Rat”) and a 10-city “Ratatouille Big Cheese Tour.”

Led by its founder, Steven Jobs, and its top officers, John Lasseter and Ed Catmull, Pixar has been ferocious in its insistence on originality through a cycle of hits that has included only one sequel, “Toy Story 2” in 1999. That policy led to a rift with its partner, Disney, which once planned its own follow-ups to Pixar films.

Disney finally backed off when it acquired Pixar last year. According to Mr. Cook, Pixar — which has agreed to make “Toy Story 3” — will now be in charge of its own sequels.

Devotion to freshness can have its price. Since the release of “Finding Nemo,” which had about $340 million in domestic ticket sales, each succeeding Pixar film, first “The Incredibles” in 2004, then “Cars” in 2006, has done less business than its predecessor.

In addition, the entertainment conglomerates that now own studios may only bring their full resources to bear on the second or third in a series of films. Next month, for instance, Disney will unveil a “massive multiplayer” online game keyed to its three “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies. This potentially lucrative enterprise took three years to develop, and would be far more difficult to build around a one-time success like “The Incredibles.”

“Branding is the word of the day and it will remain that way,” Russell Schwartz, president of New Line Cinema’s domestic marketing, said of the growing preference by audiences and the industry for known quantities.

Mr. Schwartz, whose own company had huge hits in recent years both with high-profile adaptations in the “Lord of the Rings” cycle and with an unexpected blockbuster from scratch in “The Wedding Crashers,” noted that executives would rather not depend on the latter sort of success. “There’s a zeitgeist about that kind of movie you can’t control,” he said.

The drift away from pure inventiveness is limited to the industry’s most expensive and commercial films. According to the Writers Guild of America, West, the balance between original and adapted scripts in overall feature film production has remained constant in recent years, with slightly more than half of the screenplays being original.

Old hands in the film business argue nonetheless that the industry cheats itself of something precious when it leaves the creation of its blockbuster bets to a graphic novelist like Frank Miller, whose work was behind this year’s “300,” or a distant predecessor, like the makers of the original “King Kong.”

“It’s tragic,” the screenwriter Bob Gale said of what he sees as Hollywood’s lost inventiveness. Missing, he said, is the nonpareil thrill he experienced in creating, with Robert Zemeckis, the early drafts of “Back to the Future,” a 1985 hit provoked by his own question: Would he have liked his own father if he had known him in high school?

Still, Mr. Bird confessed that pure invention can be “scary” even for those at Pixar. The director pointed, for instance, to a moment in “Ratatouille” when he felt compelled to forgo a climactic action sequence that was demanded by conventional movie logic, but that did not fit the story he and his peers had invented. “You have to let the movie be what it wants to be,” he said.

Yet that can be easier, he added, than trying to follow in the tracks of the audience. “When you just make something you want to see,” he said, “it becomes very simple.”

animated cartoons are made by artists. whatever the method the goal is the same: the illusion of life

Apr 24, 2007

Bird has the last word

Apr 16, 2007

Review: The Animated Man: a life of Walt Disney

Walt and his wife Lillian arriving in England in 1946; from "The Animated Man" by Michael Barrier

As I've written before, my respect for Michael Barrier goes back to the late 1970s when he was publishing his magazine Funnyworld. The contents were an animation fan's dream: interviews, essays, illustrations and reviews all about cartoon animation of the golden age. There was never anything close to it before, and in the decades since there's been but one similar effort, Amid Amidi's excellent Animation Blast.

It makes sense that given the huge interest in animation since the late 1980s at least one serious magazine about animation would exist now, but when Barrier was putting out Funnyworld it stood totally alone in a barren landscape of dry film journals who, if they deigned to discuss cartoons at all, usually reserved their attention for "serious", "artistic"(read: abstract, non-narrative) animation. They wouldn't have given the likes of Bob Clampett or Walt Disney the time of day unless it was as a dartboard for sexism/racism/facism/freudian subtext in cinema. Dull times indeed.

From Funnyworld I gleaned that Barrier was a stickler for facts, interested in detail, and had formed very strong views about the various studios' output. His standards of what makes good or great animation were obviously high, but he knew enough about the techniques and context of studio animation to avoid a common stumbling block I've noticed--that of comparing apples to oranges, and finding apples lacking. That is, he appreciated the Warner Bros. best output just as much as he did the best of Disney's(you'd be hard pressed to find the same broad view taken by most of the veteran artists of that age).

His last book, Hollywood Cartoons, was written with great weight given to the Disney studio--and considering the impact Disney's work had on how the world perceived animation of the so-called golden age, that made sense. It also made me eager to read Barrier's take on a man he had heard so much about from so many of his closest colleagues and employees: Walt Disney.

Since I write this blog as an animation artist and fan, and that's who I write it for, I'll put it this way: Animated Man is the book I've always wanted to read on Disney the person, and the one that I've enjoyed the most (of the two recently released and the previous few), because it's plain the author understands exactly how animated cartoons are and were made--what they are, what they can be, and how it felt to work for Walt Disney at that incredible time in history, for better or worse.

Years of research and hundreds of hours of interviews with so many artists employed by Disney clearly did that for Barrier. Although he obviously finds Walt admirable and fascinating(which he inarguably was), he never deifies him or avoids describing--through first person interviews, letters, articles and quotes--the rough edges that made up a complicated, brilliant individual. I simply don't get that feeling--that tingling at the nape of the neck, if you will--from most other authors' attempts at portraying Disney that I got from this book: that I was getting a glimpse of the real person, as much as anyone at this far remove of time and commercial ossification ever could.

A striking addition to this biography lacking in so many others is the number of long-forgotten articles in major magazines Barrier tracked down and quotes from. They're fascinating reading. Often they reveal startlingly frank descriptions of Walt's manner and appearance--much more so than one would think possible from, say, a McCalls magazine of the 1940s. It tears away the veil of reverence that's obscured the real man, resulting in Walt Disney being made over into "Uncle Walt"--a jovial, grandfatherly, completely unintimidating figure as mythical as any of his characters, if not more so.

This phony Walt, well-meant as the image might be, is terribly unfair to a man whose contradictions and flaws were just as vital to his makeup and his success as were his boundless enthusiasms, entrepreneurial spirit and imagination.

From Barrier we get neither a candy-coated view of Disney nor a fashionably po-mo slam; the context of the particular time is always clear, and made meaningful--not necessarily to Disney's benefit as an "icon", but always fair. One may occasionally wince at what one reads, but never does it ring false. Rather, it made me respect and appreciate the complete man even more--and really, really appreciate the difficulties of working for him on his greatest projects--and his failures. Since the sucess of the Disney studios depended so heavily on the contributions of many artists, we are treated to much fascinating information about those men and (few) women--including much more previously unpublished material than I expected to find. It's a biography of Walt Disney the individual, but it's also a great history of animated film production itself--since Disney virtually was his studio, as attached to it as Nemo was the Nautilus.

Certainly some of Barrier's positions buck the mainstream--one example: he feels "Mary Poppins" is a deeply flawed film. Personally I fall more into the Leonard Maltin group; despite its length and miscasting I loved the movie, as I do the completely different Travers books. Same goes for "Jungle Book"--both the film and the great novels.

But the fact is that every biographer had better have opinions, hopefully strong ones where his chosen subject is concerned. All I expect is that the author will express himself in such a way that I want to keep reading and feel I'm getting an honest context for a life--even if one or another of the author's stated opinions make me want to hurl the book across the room. Disagree though I might I never got to the hurling stage with Animated Man, and that's a tribute to the sagacity of the writing.

As a kid I interviewed some animation veterans who'd worked closely with Walt. From some of them, particularly Ward Kimball and Art Babbitt, I got much more than I expected or could process at age 17 about just how ambivalent these men's emotions were towards their onetime boss.

Their various contradictory views flummoxed me. Nothing in Bob Thomas prepared me for what they had to say, and I realized that I really had no idea of who Walt Disney was. If I'd been able to read The Animated Man beforehand it all would have made a lot more sense to me.

I have to believe that The Animated Man is the definitive book on Walt Disney's life and work, and likely to remain so for quite a while. If you have more than an average interest in Disney or animation or film production as it was from the 1920s to the 60s, this will more than suit. It's a must-have.

The Animated Man: A Life of Walt DisneyUniversity of California Press 411pp $29.95

Addendum: I can't think of anything to strongly quibble with in the book save one(and it really is but a quibble, of limited import): I think Barrier somewhat missed the boat in his description of Calarts, the instituion that Disney personally planned from the ashes of the venerable Chouinard Art School that gave the studio so many of its artists.

He describes the current campus as a "huge structure" when it's actually quite small, comprising a single building with no more then two floors of classrooms and space(I'm leaving out the notorious sublevel). Frankly the campus' five schools (film-dance-art-music-theatre) are if anything too crowded, as the building has never been substantially enlarged since its construction in the early '70s. And while Barrier points out that Walt's Calarts vision of a cross-pollinating melange didn't truly happen as he'd imagined, he doesn't mention the fact that at the very least, Calarts' music program is one of the most respected in the United States--and yes, we animation students were exposed to constant sounds of rehearsals, gamelan-jamming, jazz improvisation and dancers warming up in the shared hallways, and some cross-use between departments did occur. The theatre school too is extremely well-respected.

And without the creation of the Character Animation department (as well as Jules Engel's slightly earlier Motion Graphics department) it's more than likely that any training at all of "Disney" animation wouldn't have happened outside the studio itself, or been available to any of the lone bunch of the era who still dreamed of feature animation performance and filmmaking--of creating "the illusion of life"--being a possible, viable career.

Nevertheless, Barrier deserves credit for mentioning Calarts as being important to Walt at all as most writers on Disney completely ignore its importance in his life outside of the character animation classes' continuing additions to animation credits.

Apr 13, 2007

The Mousetrap, Part 2

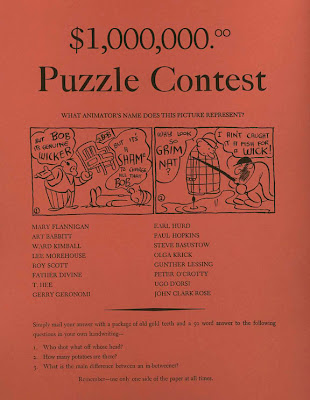

Two pages of caricatures and the inside back cover of this one-off parodical Disney magazine. Pardon the quality of the scans--the interior pages are an off white, slightly textured bond that makes for trouble in reproduction.

Some of the subjects of caricatures are well known, and a few others are unidentified by me. Anyone want to chime in on the more obscure ones?

The "undraped model" notice seems very much in the vein of Ward Kimball.

Apr 8, 2007

One weird bunny

For some reason I found this maniacal-looking rabbit a bit creepy...for me it was a bogey along the lines of that clown doll thing in "Poltergeist". And this was supposed to be a charming kid's record(my dim memories are of a generic rendition of "Here Comes Peter Cottontail" and a few weakly performed versions of songs from "Bambi")!

Looking at it now, I'm not sure why I thought it was pure evil, exactly--but I suspect a Kimball influence. Who else would design such a thing?

Apr 7, 2007

The Mousetrap, Part 1

"The Mousetrap" was a oneshot magazine that certain of the Disney artists self published in the late 1930s, before the move to the Burbank studio(I'm not sure of the exact date--anyone?).

It's a compendium of short written pieces a la the good old days of National Lampoon, leavened with caricatures and several pages of girlie drawings by Fred Moore and at least one other artist. Some of the contents have been reproduced elsewhere--most notably in "The Illusion of Life"(Ward Kimball's drawing of George Drake and Don Graham heading east in a jalopy to scout new talent; some T. Hee drawings; Fred's girls). Funnily enough, none of the contributions are signed.

Originally there were but 500 of them made and so they were extremely scarce, but around 1975 or so someone bothered to reprint it in a facsimile edition. I picked one off of a large stack at the old Collector's bookshop on Hollywood Boulevard in the late 1970s. Now both versions are rare.

With that in mind, I thought I'd post all of it here. Some of it is pretty esoteric if you're not hardcore Disney, but that's what this blog is all about, so...

I've got a fair amount of scanning and cropping to do. For a start, here's one of the back pages, with a silly gag thing by--I think--Roy Williams(I could well be wrong, so please, anyone--feel free to correct me). And another of the now-venerable girl compositions, which most of you may have seen already. Enjoy!

I'm 85% sure this is by Fred Moore--there are definitely Moore girls in the magazine--but I hadn't looked at this for years, and now it's bothering me--it's possible that they're by one of the other artists, as similar as they are to Moore's style. What do you think?

Apr 4, 2007

Pimentel--él lo hace otra vez

I hope I got the title right. It's supposed to say "he does it again".

Dave's most recent post is an upload of the drawings he was able to dash off in yesterday's gesture drawing class at Dreamworks, which he organizes. Since he spends most of the the pose time walking around, helping people out and talking to the group at large he gets little time to draw himself, so the drawings posted aren't cherry-picked. Lots to learn by looking at them, I think...also, it's my favorite model. She's a girl who has a terrific sense of grace and action in posing, and is blessed with a form that is beautifully proportioned--perfect for animation.